How to Detect and Analyze DDoS Attacks Using Log Analysis

The cloud delivers many benefits to companies and users alike, but it has one clear disadvantage: its vulnerability to cyber threats. This was brought to light this past December. Linode – a Linux cloud hosting provider – suffered from a massive attack that lasted 10 days. The DDoS attack targeted numerous systems including nameservers, application servers, and routers. It even led to a suspected account breach forcing Linode’s users to reset their passwords.

Why Did This Happen to Linode?

One of the first things a company asks after an attack is “Why me?” Cloud providers are a perfect target because they host several services and always contain personal data such as a user’s address, phone number, credit card number, and other sensitive information. Linode offers cloud infrastructure for remote customers in need of Linux servers. Integrating IaaS (Infrastructure-as-a-Service) services makes a cloud service a critical part of business performance, so taking out Linode cripples its customers’ performance as well. Linode doesn’t know the motive behind the attack, but the attacker’s persistence was evident. The attack,intended to cripple Linode’s services and disrupt customer activity, was a success and classified as highly sophisticated by Linode and other security experts. The attack spanned several locations and was so persistent that Linode was forced to block certain geolocations including South America, Asia, and the Middle East. This is the type of critical mitigation techniques some companies are forced to use to stop an attack. DDoS attacks are much more effective than other attacks since they are coordinated attacks using thousands of machines. It’s not as difficult to penetrate resources using brute-force password attacks or SQL injection. The latter types of attacks can set off alerts, but a DDoS attack comes swiftly and without notice. The biggest DDoS attack to date was performed on the BBC sending it over 600Gbps in traffic.

How Is a DDoS Organized?

Before we get into ways to identify a DDoS attack, it’s important to understand how they are organized and work. Decades ago, a few machines were enough to crash a web server. Now with expanded bandwidth and faster computer resources, attackers need thousands of machines to flood a server with traffic. Attackers use botnets, which comprise thousands of zombie machines that are hacked individual PCs or servers. These PCs have malware installed on them and give the attacker the ability to control the machines from one remote location. Attackers are able to install malware on a remote machine through malicious software included in phishing emails or using web pages called “Java drive-by pages.” If the attacker can trick the user into allowing the Java code to run, he can infect the machine with various rootkits and trojans. The infected zombie machines give total control to the hacker. When the hacker is ready to attack, he signals the legions of zombie machines to flood a specific target. For well-structured infrastructure, the hacker could fail. However, most attacks are successful at some level either harming service performance or breaching security. Hackers also have several choices in the type of DDoS they use. SYN attacks are most commonly used in large attacks. With smaller attacks, companies can add more bandwidth and server resources, but DDoS attacks continue to increase in bandwidth and duration. Small site owners only purchase hosting services that allow a few thousand concurrent connections, but attackers can simulate 100,000 connections with an effective botnet.

How to Detect an Active Attack on Your Server

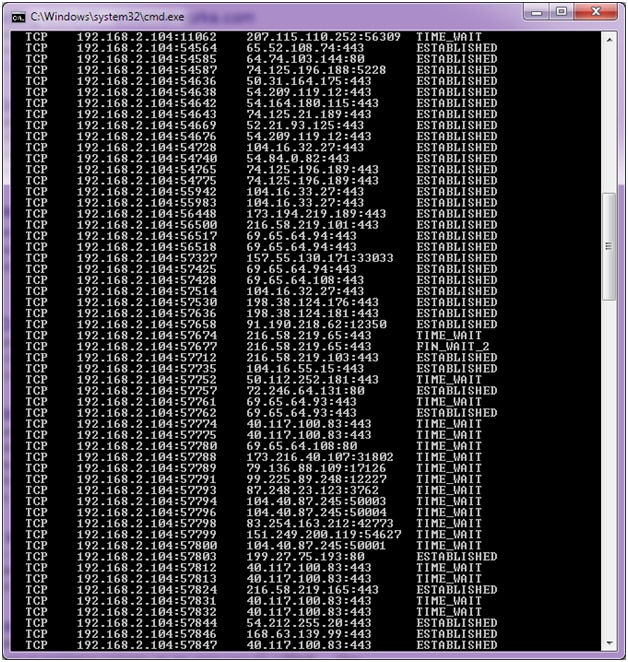

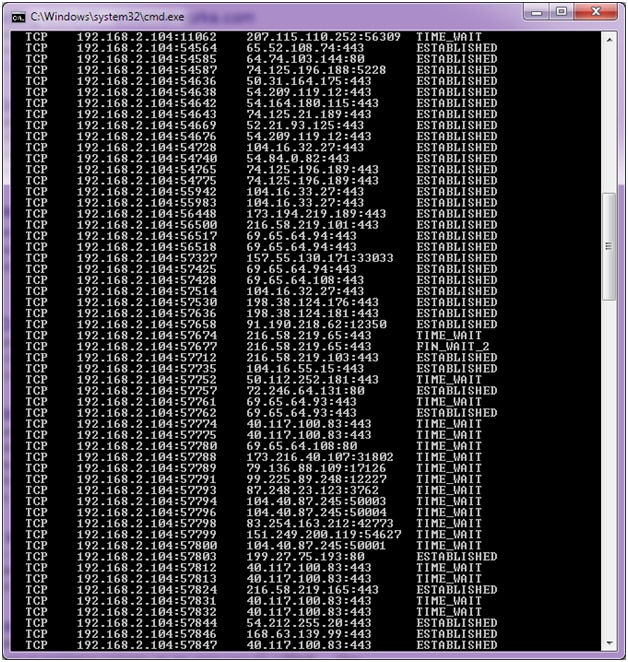

DDoS attacks are quick to start killing performance on the server. The first clue that you’re under an attack is a server crash. With IIS, the server often returns a 503 “Service Unavailable” error. It usually starts intermittently displaying this error, but heavy attacks lead to permanent 503 server responses for all of your users. Another hint is that the server might not completely crash, but services become too slow for production. It could take several minutes to submit a form or even render a page. Whether you have the inclination that your server is under attack or you’re just curious about its stats, you can start an investigation using Netstat. Netstat is a utility included in any Windows operating system. Open a Windows command prompt and type “netstat –an.” Standard output should look like the following:  The above image illustrates the way your server would look. You see multiple different IP addresses connected to specific ports.Now take a look at what a DDoS attack would look like if the server was attacked.

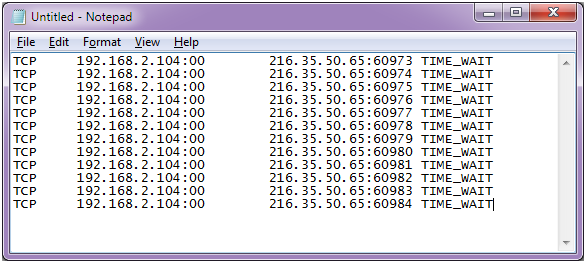

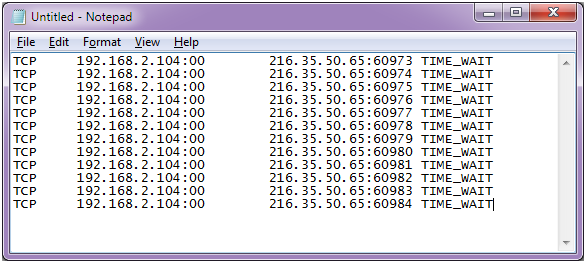

The above image illustrates the way your server would look. You see multiple different IP addresses connected to specific ports.Now take a look at what a DDoS attack would look like if the server was attacked.  We simulated an example in a text file since we can’t get sample output from Netstat. The takeaway from this screenshot is that the same IP is connecting to contiguous ports and the connection is timing out. We show only a handful, but a real DDoS attack should show hundreds of connections (sometimes thousands). Once you’ve confirmed that you have a DDoS attack in progress, it’s time to review server logs. You can pull raw logs from Microsoft IIS, or you can use a log analyzer. Log analyzers provide visual details for your web traffic. In this example, we have the IP address for at least one attacker, but we need to see most of them. Loggly gives you quick statistics on your site traffic. You can get a free trial account here.

We simulated an example in a text file since we can’t get sample output from Netstat. The takeaway from this screenshot is that the same IP is connecting to contiguous ports and the connection is timing out. We show only a handful, but a real DDoS attack should show hundreds of connections (sometimes thousands). Once you’ve confirmed that you have a DDoS attack in progress, it’s time to review server logs. You can pull raw logs from Microsoft IIS, or you can use a log analyzer. Log analyzers provide visual details for your web traffic. In this example, we have the IP address for at least one attacker, but we need to see most of them. Loggly gives you quick statistics on your site traffic. You can get a free trial account here.  Again, the image shows normal traffic, but what you’re looking for is huge spikes in activity. This tells you the time the attack started, so you can go back to your server logs and review IP activity. Since a DDoS attack is an incredible amount of traffic sent to your server, you would see a spike unlike any high-traffic day including your busiest times. As a matter of fact, the ideal time for an attacker to strike is when you’re busy, because he can use the existing traffic as well as his own to help crash the server. Luckily, Loggly has a tool for anomaly detection. In the trends tab toolbar, you’ll find the option to view anomalies.

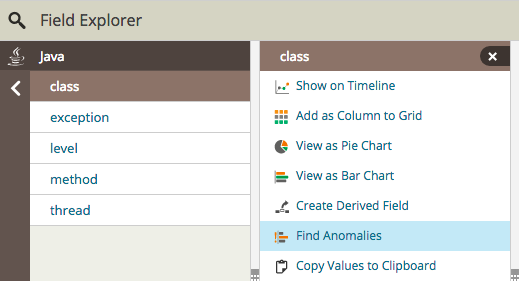

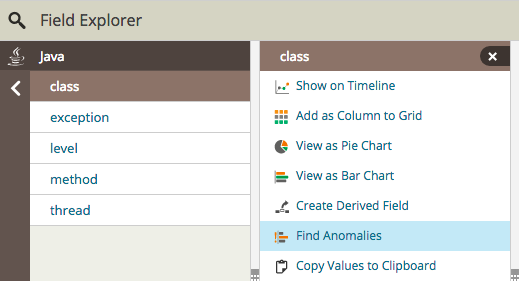

Again, the image shows normal traffic, but what you’re looking for is huge spikes in activity. This tells you the time the attack started, so you can go back to your server logs and review IP activity. Since a DDoS attack is an incredible amount of traffic sent to your server, you would see a spike unlike any high-traffic day including your busiest times. As a matter of fact, the ideal time for an attacker to strike is when you’re busy, because he can use the existing traffic as well as his own to help crash the server. Luckily, Loggly has a tool for anomaly detection. In the trends tab toolbar, you’ll find the option to view anomalies.  Click “Find Anomalies” and you’ll see a screen similar to the following image:

Click “Find Anomalies” and you’ll see a screen similar to the following image:  In this image, you’ll see that there is an increase in 503 status codes. Remember that a DDoS attack usually renders the IIS server unavailable, and it shows as a 503 to your site visitors and in your IIS logs. If you want to view raw logs, you can find your IIS log files in the “C:inetpublogsLogFilesW3SVC1” directory. Of course, this assumes that you’re using IIS in its default directory. The log files are basic text files that you can use to review traffic. They aren’t easy to read without any parsing. You can also use third-party logging libraries in your .NET projects. The following image is an example log file from IIS:

In this image, you’ll see that there is an increase in 503 status codes. Remember that a DDoS attack usually renders the IIS server unavailable, and it shows as a 503 to your site visitors and in your IIS logs. If you want to view raw logs, you can find your IIS log files in the “C:inetpublogsLogFilesW3SVC1” directory. Of course, this assumes that you’re using IIS in its default directory. The log files are basic text files that you can use to review traffic. They aren’t easy to read without any parsing. You can also use third-party logging libraries in your .NET projects. The following image is an example log file from IIS:  Since we found the spike in traffic from our Loggly analysis, we can now identify the IP addresses in the IIS logs based on the time span of the attack.

Since we found the spike in traffic from our Loggly analysis, we can now identify the IP addresses in the IIS logs based on the time span of the attack.

What Should You Do to Stop the Attack?

Remember that the attacking machines typically belong to innocent people who don’t know that their computers have malware. You can report the offense to the attacker’s ISP abuse department. Usually, the abuse email is “abuse@.” This could at least stop some of the attacks, but this takes time and doesn’t help you right now. Attacks are stopped at the router. With a Windows server, you can also use the system firewall included with the operating system. You can read how to set up filters in Windows in this article . If you don’t have control of the routers – which is the case if you have cloud hosting – then the emergency step would be to block traffic in the Windows firewall and contact your host. Some CDN cloud providers offer DDoS protection. CloudFlare is a popular performance and security company that offers good protection against even sophisticated attacks. You can choose any intrusion detection software, routing configurations, and even a CDN to mitigate DDoS attacks. However, very sophisticated attacks sometimes get through these defenses. It’s important to monitor your traffic, and Loggly helps save you time by giving you a graphical image and chart that you can use to quickly notice one of these attacks. With Loggly, you just need a few minutes each day to review any unusual traffic. Don’t spend another minute trying to figure out if you are under a DDoS attack, click to sign-up for a free 14 day log analysis account. Related Posts:

The Loggly and SolarWinds trademarks, service marks, and logos are the exclusive property of SolarWinds Worldwide, LLC or its affiliates. All other trademarks are the property of their respective owners.

Jennifer Marsh

The above image illustrates the way your server would look. You see multiple different IP addresses connected to specific ports.Now take a look at what a DDoS attack would look like if the server was attacked.

The above image illustrates the way your server would look. You see multiple different IP addresses connected to specific ports.Now take a look at what a DDoS attack would look like if the server was attacked.  We simulated an example in a text file since we can’t get sample output from Netstat. The takeaway from this screenshot is that the same IP is connecting to contiguous ports and the connection is timing out. We show only a handful, but a real DDoS attack should show hundreds of connections (sometimes thousands). Once you’ve confirmed that you have a DDoS attack in progress, it’s time to review server logs. You can pull raw logs from Microsoft IIS, or you can use a log analyzer. Log analyzers provide visual details for your web traffic. In this example, we have the IP address for at least one attacker, but we need to see most of them. Loggly gives you quick statistics on your site traffic. You can get a free trial account here.

We simulated an example in a text file since we can’t get sample output from Netstat. The takeaway from this screenshot is that the same IP is connecting to contiguous ports and the connection is timing out. We show only a handful, but a real DDoS attack should show hundreds of connections (sometimes thousands). Once you’ve confirmed that you have a DDoS attack in progress, it’s time to review server logs. You can pull raw logs from Microsoft IIS, or you can use a log analyzer. Log analyzers provide visual details for your web traffic. In this example, we have the IP address for at least one attacker, but we need to see most of them. Loggly gives you quick statistics on your site traffic. You can get a free trial account here.  Again, the image shows normal traffic, but what you’re looking for is huge spikes in activity. This tells you the time the attack started, so you can go back to your server logs and review IP activity. Since a DDoS attack is an incredible amount of traffic sent to your server, you would see a spike unlike any high-traffic day including your busiest times. As a matter of fact, the ideal time for an attacker to strike is when you’re busy, because he can use the existing traffic as well as his own to help crash the server. Luckily, Loggly has a tool for anomaly detection. In the trends tab toolbar, you’ll find the option to view anomalies.

Again, the image shows normal traffic, but what you’re looking for is huge spikes in activity. This tells you the time the attack started, so you can go back to your server logs and review IP activity. Since a DDoS attack is an incredible amount of traffic sent to your server, you would see a spike unlike any high-traffic day including your busiest times. As a matter of fact, the ideal time for an attacker to strike is when you’re busy, because he can use the existing traffic as well as his own to help crash the server. Luckily, Loggly has a tool for anomaly detection. In the trends tab toolbar, you’ll find the option to view anomalies.  Click “Find Anomalies” and you’ll see a screen similar to the following image:

Click “Find Anomalies” and you’ll see a screen similar to the following image:  In this image, you’ll see that there is an increase in 503 status codes. Remember that a DDoS attack usually renders the IIS server unavailable, and it shows as a 503 to your site visitors and in your IIS logs. If you want to view raw logs, you can find your IIS log files in the “C:inetpublogsLogFilesW3SVC1” directory. Of course, this assumes that you’re using IIS in its default directory. The log files are basic text files that you can use to review traffic. They aren’t easy to read without any parsing. You can also use third-party logging libraries in your .NET projects. The following image is an example log file from IIS:

In this image, you’ll see that there is an increase in 503 status codes. Remember that a DDoS attack usually renders the IIS server unavailable, and it shows as a 503 to your site visitors and in your IIS logs. If you want to view raw logs, you can find your IIS log files in the “C:inetpublogsLogFilesW3SVC1” directory. Of course, this assumes that you’re using IIS in its default directory. The log files are basic text files that you can use to review traffic. They aren’t easy to read without any parsing. You can also use third-party logging libraries in your .NET projects. The following image is an example log file from IIS:  Since we found the spike in traffic from our Loggly analysis, we can now identify the IP addresses in the IIS logs based on the time span of the attack.

Since we found the spike in traffic from our Loggly analysis, we can now identify the IP addresses in the IIS logs based on the time span of the attack.